From Section II of Kant's unpublished draft introduction to the Critique of Judgment:

II. On the system of the higher cognitive facilities, which grounds philosophy

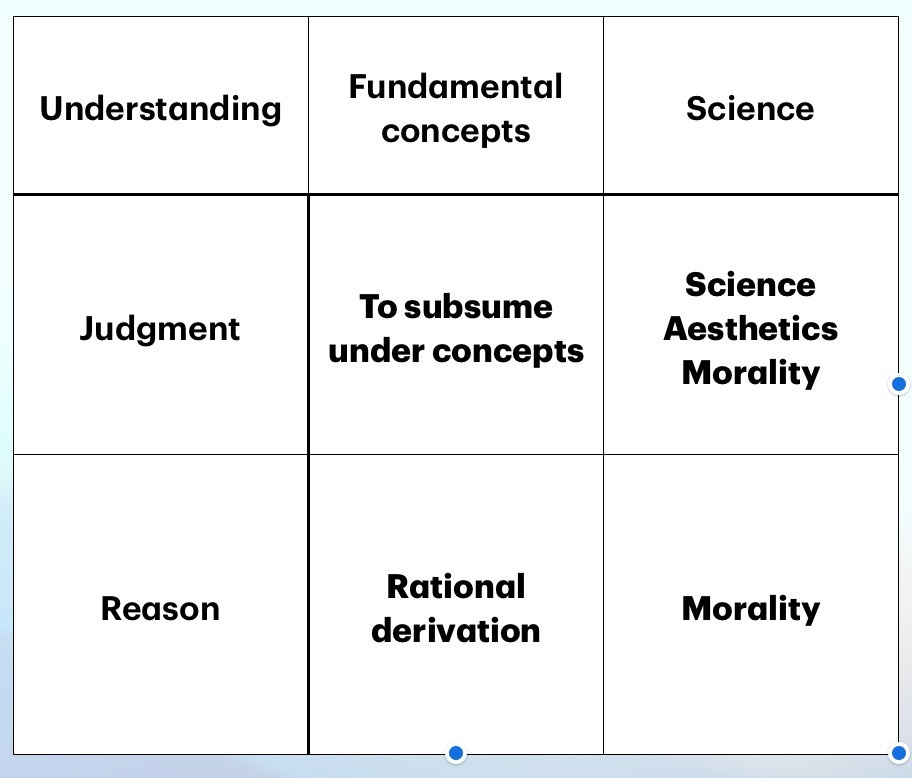

If the issue is not the division of a philosophy, but of our faculty of a priori cognition through concepts . . . then the systematic representation of the faculty for thinking is tripartite: namely, first, the faculty for the cognition of the general (of rues), the understanding; second, the faculty for the subsumption of the particular under the general, the power of judgment; and third, the faculty for the determination of the particular through the general (for the derivation from principles), i.e., reason.

So if before, in the previous essay, we distinguished two kinds of philosophies, a natural metaphysics and a moral metaphysics, then here we step back and examine different ways of cognitions, i.e., different ways of thinking and knowing, or the different ways in which we apply our minds, each having its own functionality.

Any judgment whatsoever—the earth is round, charity is noble, the Mona Lisa is a beautiful picture—requires the stringing together of concepts, minimally, connecting a subject concept to a predicate concept. The Critique of Pure Reason dealt with the most a general of concepts which enable us to have any experience whatsoever, e.g., concepts of quality, quantity, cause and effect, etc., and it also dealt, at least in part, with judgments with regard to understanding nature. The Critique of Practical Reason dealt with reason. We need concepts in order to understand what we see, but we also need reason in order to understand what we ought to do, both what we ought to do with the knowledge gleaned from nature and what we ought to do for its own sake. Judgments of fact concern understanding mechanical or efficient causes in nature, how nature operates, and moral judgments concern how we ought to behave towards one another as rational human beings, not just what we ought to do to satisfy our own personal inclinations. We thus have judgments concerning efficient causes, what makes things work, and final causes, what should I cause to happen or what motivations should demand my action and attention.

This is all very good when we connect our judgments to some sort of cause or another, but what if we detach those judgments from any such cause so that we have neither a speculative or theoretical judgment nor a practical judgment. In this third critique, Kant begins with these first two judgments in order to arrive at a third type that concerns judging in its purest form, detached from all cause and purpose. What could such a detached judgment be?

Consider: That flower is beautiful. Yes the flower is caused by something, by a gardener who planted a seed, but a judgment of beauty isn't about how the flowe got there. Perhaps nature has endowed this flower with a purpose or function of attracting bees and propagating its species, but the judgment of beauty doesn't address what the flower is for. This is an example of a judgment that is detached from efficient and final causes.

Kant refers to this as a “reflective judgment” and distinguishes it from those causally influenced “theoretical judgments.” It is not the only kind. He gives other examples, such as techniques we use to regulate our scientific investigations. An example would be Occam's razor, that the simplest answer is most likely the correct answer. There's no reason to believe that this principle is correct about nature, but it can be very useful in helping us choose between scientific models. We might choose a model that's less perfect just because it's simpler and easier to use, but he argues that these kinds of judgments are ones we give to nature not ones we learn from nature. Scientific investigation would be impossible without us giving some principle or some criteria to our investigation in advance of the investigation. Whether or not the flower’s purpose is to propagate itself, according to the theory of evolution, some sort of principle must be established first. If it were, for example, determined that the theory of evolution is false, then we would have to describe some other purpose for the existence of flowers in order to conduct a search for that purpose.

Now it comes to mind that such criteria, essentially regulative rules which regulate our investigations, do not in fact seem disinterested. They have the purpose to enable said investigation in the first place. Perhaps the difference is that the interest in these cases of reflective judgment or subjective rather than object objective.

Postscript: Today, philosophy is its own academic department, distinct from science, but in the 18th century, “science” referred to any academic discipline, so theology, for example, could be considered a science. Meanwhile, natural science was synonymous with natural philosophy, that is, the latter was simply a branch of philosophy. Thus, by rescuing philosophy, Kant rescues natural science; further, by making rational cognition about understanding nature, Kant starts the path of separating out today's notion of natural science from today's notion of cognitive philosophies (logic, positivism, etc.) in which the latter serve as critiques of our cognitive systems that support natural science. These cognitive philosophies have sometimes been derided as the““handmaidens of science,” and we have Kant to think for that.